The Angkor archaeological complex in Cambodia is one of the most impressive and iconic archaeological sites in the world. Stretching over 400 square kilometers, it was once the center of the Khmer Empire, a powerful civilization that controlled much of Southeast Asia from the 9th to the 15th century AD. Today, Angkor is a UNESCO World Heritage site, attracting millions of visitors each year.

If you’re fascinated by ancient architecture, history, and culture, then Angkor is a must-visit destination. This article will explore the architectural marvels of Angkor, including the famous temples, palaces, and other structures that make up this incredible complex.

The Temples

Undoubtedly, the temples of Angkor are the most famous and impressive structures in the complex. These temples are known for their intricate carvings, towering spires, and imposing presence. The most famous of these temples is Angkor Wat, a massive temple complex that covers over 160 hectares!

Angkor Wat is believed to have been built in the early 12th century, and it remains the largest religious monument in the world. Its design is a masterpiece of Khmer architecture, with its five towers representing the five peaks of Mount Meru, the home of the gods in Hindu mythology. Other notable temples in the Angkor complex include Bayon Temple, Preah Khan, and Ta Prohm, each with its unique design and atmosphere.

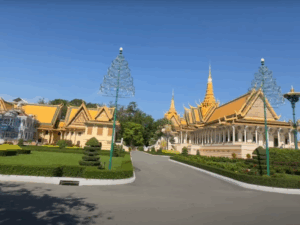

The Palaces

The temples might get all the attention, but the Angkor complex also contains several impressive palaces. One of the most noteworthy is the royal palace of Angkor Thom, which was the capital city of the Khmer Empire. This massive complex includes a palace, a temple, and several other structures, all enclosed by a massive wall and moat.

Other noteworthy palaces in Angkor include the Palace of the Leper King, which features impressive carvings and intricate design, and the Terrace of the Elephants, which was used for royal processions and ceremonies.

The Water Management System

The Khmer Empire was known for its advanced water management systems, which allowed it to control and irrigate vast areas of land. In Angkor, this system was especially impressive, with a series of canals, reservoirs, and aqueducts that still function today.

One of the most impressive parts of this system is the Baray, a series of massive reservoirs that can hold over 8 billion liters of water. These reservoirs were used to store water during the rainy season, ensuring a steady water supply for crops and other needs. The Baray was also used for religious and cultural purposes, with some temples and palaces being built on its shores.

The Hydraulic Engineering

The Khmer Empire was also known for its incredible hydraulic engineering feats, including the use of complex aqueducts and reservoirs. In Angkor, one of the most impressive feats of hydraulic engineering is the Western Baray, a massive man-made lake that covers over 2,200 hectares!

This lake was created by a series of dams and canals, and it was used for irrigation, transportation, and as a defensive measure. Incredibly, the Western Baray is still in use today, providing water to farmers and communities in the area.

The Angkor complex is one of the most impressive and awe-inspiring archaeological sites in the world. Whether you’re interested in ancient architecture, history, or culture, there’s something for everyone in Angkor. From the iconic temples to the impressive water management systems and hydraulic engineering feats, every part of this complex is a testament to the ingenuity and creativity of the Khmer Empire.

If you ever get the chance to visit Angkor, make sure to take your time and explore every corner of this incredible complex. You won’t be disappointed!

- Uncover Cambodia’s Hidden Charms 6 Days / 5 Nights (178 views)

- The Best Exotic Vietnam – 16 Days / 15 Nights (121 views)

- The 10 Best Tour Operators in Vietnam for 2026: An Expert, Objective Review (119 views)

- Seamless Cruise: Halong Bay to Da Nang – Fostering smooth travel experience from Halong Bay to Da Nang. (89 views)

- Discover the Enchanting Culture of Hanoi in Every Sense (81 views)